Genetic terminology has a rich history that recalls the continuing evolution in our understanding of genetics, DNA, and DNA inheritance over the last century. As scientists first observed differences in the appearance of animals and plants, and their inheritance patterns, they proposed the idea of locations of “factors,” later called genes, and developed terms for describing what they could observe through classical, or traditional, experimentation and observation methods. With the advent of molecular genetics and whole-genome studies, new terminology arose to describe in detail the exact type of DNA variation found.

These two versions of genetic terminology, classic and modern, are still used in tandem today. Each have different advantages and disadvantages, and both can be found in Wisdom Panel™ breeder reports’ individual results and in Litter Predict. To first learn about basic genetic terminology and inheritance, read our “Genetics Terms and Concepts 101” blog.

Classical Genetics Terminology

Classical allele terminology is often the go-to type when scientists communicate genetic concepts to breeders, pet owners, or even the lay public about their own genetic results. This is because classic terms represent those concepts to a broad audience more easily. The term locus (plural: loci), from Latin, "place,” was used before people knew the molecular structure of DNA, but did understand that chromosomes, observable with a microscope, were involved in inheritance. Scientists theorised that genes performed certain observable functions and were located at loci, or specific sites on chromosomes. They called the variation at these locations alleles, from the Greek for “alternative forms.”

Classic Allele Names

To represent the “alternative forms” scientists like Gregor Mendel observed in trait inheritance, for example, pink and white sweet peas, or tall and short plants. Researchers assigned allele names with letters, and alleles occurring at the same locus or gene were given similar names, often related to the name of the gene. Scientists also saw that some alleles were dominant to others and prevented the expression of recessive alleles. To describe the mode of inheritance, and the relationship between alleles, an arrangement of the alleles at a locus from most to least dominant was called a series. We still use these terms regularly for genes with many alleles or variants.

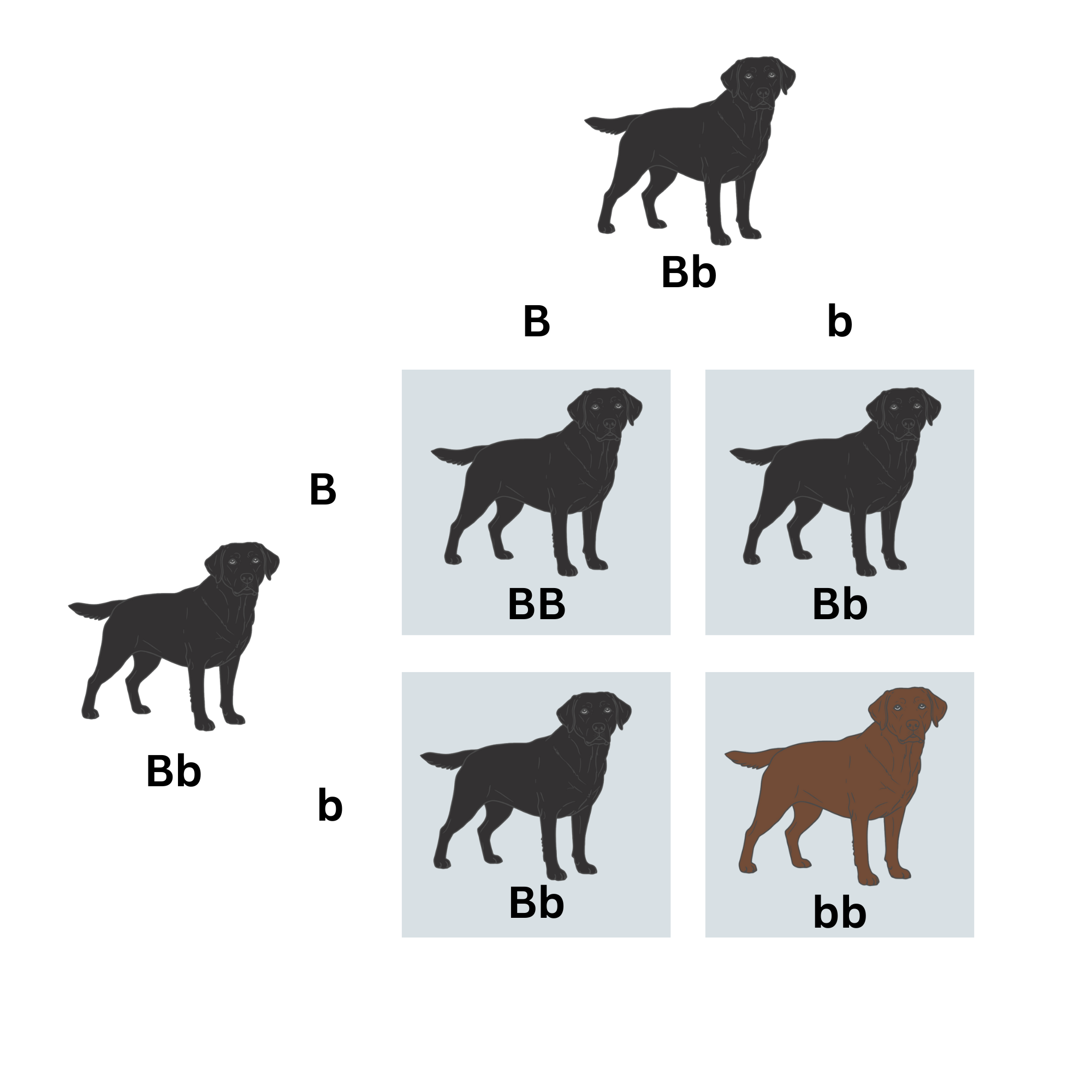

To take an example from canine genetics, the Brown Locus, which we now know houses the TYRP1 gene, was known to be responsible for chocolate, brown, or liver colouration in dogs. By examining pedigree, we knew that black colouration was dominant to brown. Therefore, the “Black form,” or allele, was assigned the capital letter “B” for the dominant allele at the Brown Locus, and all alleles causing brown or chocolate were represented with a lower case “b.” If more than one dominant or recessive allele is known, they are given superscripts. In Wisdom Panel canine breeder tests, there are 6 alleles for chocolate:

bd, basd, bc, bs, be, and bh

Modern Genetic Terminology

In 1952, Rosalind Franklin discovered the double-helix molecular structure of DNA. A year later, Watson and Crick formalised our modern concept of DNA in an historic publication describing DNA as a double-helix, with a sugar-phosphate backbone, and pairings of four types of nucleotides. With these findings, a new, modern language to describe DNA, inheritance, and variation was born.

Our modern naming system for genetic variation in dogs was formalised with the completion of the first dog genome map of a Boxer dog named Tasha in the summer of 2004. Many researchers contributed to the Dog Genome Project, including Wisdom Panel’s founders. A genome is the full set of DNA information contained within an individual, and once mapped, functions just as it sounds—it provides a genetic “map” and a shared common language that scientists can use to talk about dog DNA variation, where it is, and what it does. We’re still learning about the differences between breeds and within individuals, and to date, more than 33 million variants have been found between breeds.

Modern Allele Names

With a dog genome map in hand, we can now talk about variations in dog DNA in terms of the specific code or nucleic acid change that took place, and where it occurred. We can then talk about how this change in turn affects the protein produced. That’s important, because the protein is where the “rubber meets the road,” or how the DNA change has its effect.

Taking the original example of the Brown Locus, in modern genetics terminology, we’d refer to the B Locus as the TYRP1 gene located at Canis familiaris autosome 11, or CFA11:33,376,152-33,394,014. If we picked one of the chocolate variants, bd, we could then describe it as:

bd: c.1033_1035del (p.Pro345del)

To break this down, bd is in the TYRP1 gene on chromosome 11, and “c” represents the DNA code change, in this case, a deletion or loss of 3 letters of the DNA code from position 1033 to 1035 in the gene. This results in a protein (“p”) change, the deletion or loss of a proline (“Pro”) amino acid at position 345. The shorthand expression then for the bd variant would be “D” or “deletion,” and since the bd variant is not what’s found in wild dogs and wolves, it would be called the mutant or derived variant, while the B variant would be called “wild type” or wt.

Why Wisdom Panel testing uses both Classic and Modern Genetic Terms

You can see that in the example of the Brown Locus, although the modern allele name for bd is perfect for differentiating this specific variant of brown from all others, it’s not easily used to convey the concept of “chocolate” for an owner or breeder receiving results. It does, however, let us know that this is a deletion at position 1033, so bd can and does occur at times on the same chromosome as ba, which occurs at a different position in the TYRP1 gene. In practical terms, this means that breeders who receive a result with two or more copies of b alleles should beware if one or more of those is a bd allele, as it may have been donated by the same parent. That would mean the general rule that two recessive copies of a variant inherited means the dog will express the variant doesn’t apply in this case, as one parent may have contributed the dominant variant, cancelling out the effects of the two recessive copies from the other parent.

Because Wisdom Panel scientists design our custom DNA chips, they must use the modern terminology for precision and accuracy in design. Results should clearly show what was tested when reporting disorder results to kennel clubs or open health registries to ensure that the results from various testing labs are equivalent. That’s why when viewing your animal’s Complete Genetic Report, we list gene, variant, and copy number for disorders. When communicating results for tools like trait predictions in Litter Predict, however, it’s much easier to communicate the inherited genotype of a potential sire or dam in terms of the classic alleles, such as B/b. Below is a comparison of classic vs. modern terminology differences, using our example of a trait, Brown, also called chocolate or liver:

|

Term |

Classical |

Modern |

|

Location of genes |

B Locus |

Chromosome number, numeric position based on genome assembly for species, e.g. CFA11:33,376,152-33,394,014 |

|

How genes are named |

Named for trait, e.g. “Brown” |

Named for molecular function, e.g. Tyrosinate related protein 1 or “TYRP1” |

|

Variation at a gene |

Allele |

Variant, mutation |

|

Method of describing variation at a gene |

Upper and lowercase letters, e.g. B, bd |

Specific type of mutation found, e.g. “deletion,” “insertion,” “T>G,” “C>T” or “derived” and “wild type.” |

|

How inheritance is described |

Simple Mendelian (recessive, dominant, co-dominant, semi-dominant) |

Simple, as well as complex, with variation in penetrance, risk, expression |

Differences in reporting between testing services

In addition to the benefits and differences in use of the types of genetic terminology within Wisdom Panel, there is sometimes a lack of consensus within the scientific community for how known variation should be named, or the disorder or trait associated with it. Often this is due to differing opinions on what most clearly communicates the results or the original breed context for the discovery, but sometimes an evolving understanding of the variant or gene also plays a role. Below is a list of some of the common variations seen in trait reporting:

|

Trait |

Wisdom Panel™ Breeder Derived Variant |

Wisdom Panel™ Breeder Wild Type |

Modern Allele Derived Variant |

Modern Allele Wild Type |

Classic Allele Variant |

Classic Allele Wild Type |

|

Albino |

caL |

C |

A |

G |

|

|

|

Back Bulk |

BULK |

wt |

T |

C |

|

|

|

Bobtail |

T |

wt |

C |

G |

|

|

|

Cocoa |

co |

WT |

|

|

|

|

|

Curl |

C |

c |

T |

C |

|

|

|

Ear Carriage |

FLOP |

prick |

C |

T |

|

|

|

Furnishings |

F |

f |

|

|

F |

IC (improper coat) |

|

Reduced Shedding |

shed |

SHED |

T |

C |

SD, N*, n*, SD, sd |

N, sh*, SD*, SD |

|

Ridge |

R |

r |

dup |

- |

|

|

|

Roan |

Tr |

tr |

|

|

R, T, TR |

r, t, tr |

|

Saddle Tan |

ST |

st |

|

|

ASIP^BS, II, BS |

|

Final Thoughts

The field of veterinary genetics is relatively new, with rapid expansion in our knowledge, and with it, a changing jargon. As genetics touches all of us, it makes sense that there are various methods of communicating genetic information depending on the audience and purpose. The two versions of genetic terminology, classic and modern, used in Wisdom Panel breeder reports’ individual results and in Litter Predict are meant to convey the information in the clearest possible way for the most common usage.